Racism Matters, but to Whom?

Racism Matters, but to Whom?

by Beyon Miloyan

The killing of George Floyd has recently brought racism back into the headlines. It is not easy to distinguish opposition to the Black Lives Matter movement from anti-black sentiment, but the public and mainstream media have tended to combine these views, with discourse concentrated on the idea that racial injustice has been at the core of Western society since the European colonization of the Americas and the Western perpetration of slavery.

But Greece and Serbia abolished slavery in 1832 and 1835, the United Kingdom and France in 1833 and 1848, and the US in 1865, although Ohio, New Jersey, Michigan, Indiana, New York, Illinois and Pennsylvania had all abolished slavery at various times over the preceding decades, starting with Ohio in 1802. The abolishment of slavery did not happen all at once, neither worldwide nor within countries.

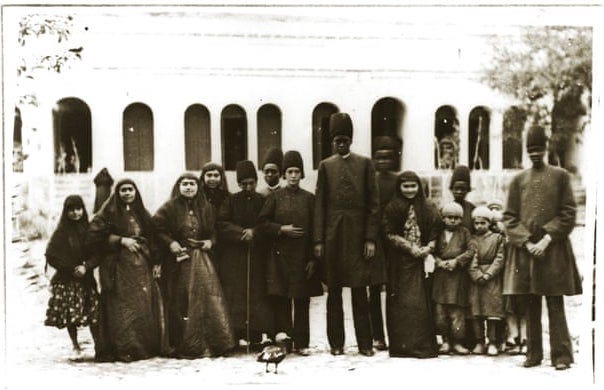

It was the non-Western countries — Cameroon, Siam, Morocco, Afghanistan, Turkey, Nigeria, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and others whose natives and descendants are now mostly treated as victims of racism in the West — who did not abolish slavery until the 20th century. Same with Iran, where black people served as (castrated) servants for wives in the harems of high-ranking officials in the Qajar empire. In contrast to Western slavery, the Qajar harems also contained Christian women who were abducted in wars with Russia and Georgia. Take for example the case of “Gul-Pirhan” Khanum, the Armenian captive from Tiflis who was forced to become one of the 165 wives of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar.

A Qajar Harem, 1883. (Photo Archive, Golestan Palace Museum, Tehran, Iran)

Nine years after the US Civil War, the Armenian novelist and Iranian native Raffi (Hakob Melik-Hakobian) published his novella Harem, a story about black, female and Armenian liberation from Qajar captivity that I recently co-translated to English. The book was published in Tiflis (then part of the Russian Empire), but as a result of its publication, Raffi was threatened with death and exiled from Iran. Set in Tehran at the turn of the 19th century, the novel follows the story of “Zeynep” Khanum, an Armenian captive from Tiflis who is forced to join the royal harem as a wife of the Iranian prince, but has secretly maintained her Armenian and Christian heritage. The story involves mutual efforts between black and Armenian slaves in the harem to liberate each other from captivity, and it is Marjan — the black slave and heroine — who masterminds the escape, after her faithful mistress Zeynep promises to free her if she succeeds in finding an escape route.

Despite Raffi himself having been secular, it is not a coincidence that the character of Zeynep (the oppressed liberator) is Christian. As François Benoux observed, almost every major abolition movement was Christian-inspired, which is not only true of the famous black US abolitionists, such as Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, who fought for the freedom of their own people, but also the outstanding Quaker abolitionists — Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Chandler and the Grimké sisters. In England, Olaudah Equiano, Charles Spurgeon, William Wilberforce and John Wesley were among the most notable abolitionists, and in the Catholic Church, Popes Benedict XIV and Gregory XVI condemned slavery in 1741 and 1831. Even Charles Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus — who was both a Christian and an evolutionary theorist — was publicly and proactively opposed to the slave trade. Yet his better-known grandson who inherited only the evolutionary theorizing had little to say on the matter, except that slavery was bad. The earliest and most significant stands against slavery in and after the Industrial Revolution were taken by Christians.

And yet some people (among whom, popular academics like Steven Pinker) contend that abolition movements were born of scientific progress, when in fact scientific racism grew following the wave of 19th century abolition in the West: We see this for example with the establishment of Sweden’s State Institute for Racial Biology in 1922 (funded by the Nobel foundation), Mussolini’s speeches and policies in the 1930s (backed by the work of Julius Evola), and the scientifically-supported Jewish Holocaust of the 1940s by the Nazi regime. In the US, Henry Goddard perniciously adopted Alfred Binet’s intelligence (IQ) test to inform decisions about immigration policy, sparking a new domain of psychometric testing and igniting the spread of the persistent and harmful illusion that IQ testing ought to be used to identify those who are (or should be) given the greatest opportunity to make it into the upper echelons of society. Binet’s test was developed expressly to identify children in need of special education, and did not presume to capture those with superior mental abilities. Nonetheless, since Goddard’s adoption, IQ tests have been used worldwide for this purpose in the name of “science” — a bait-and-switch that was recently debunked by Nassim Taleb.

The academies have failed us. They have supplied and validated false and politically expedient narratives of racism’s historical and current causes, while propagating the (pseudo)scientific tools that are used to legitimize racism — “Feeding the hen with one hand, and taking her eggs with the other,” as the Armenian proverb goes. And yet, following George Floyd’s death, our attention has been deflected almost entirely from these faults, with the anti-racism initiative now bundled with anti-establishment positions that include defunding the police, weakening Christianity and disrupting the nuclear family structure — positions that are antithetical to the anti-racism cause, and are alarmingly supported by the establishment itself. Racism, oppression and slavery are far too important to be used as pawns in political games — and if not the educational institutions, NGOs and mainstream media, who today will take responsibility for deconstructing these rampant false narratives?